Amy Henry and I met on Facebook. We share a love of history and historical fiction, and we are both writers. I wish we could meet for coffee and maybe a manuscript critique, but we live 1,500 miles apart!

While my writing is almost exclusively for children, Amy writes for an adult audience. You can read a teaser for her intriguing WWII novel, The Sticking Place, on her website https://amyhenrybooks.com/about-the-bookexcerpt/ You’ll also find links to two of her published short stories here: https://amyhenrybooks.com/publications-awards/

--------------------------

So ... Amy ...

Thanks for letting me interview you. The reason I've dragged you into this is to pick your brain about writing.

Q: On your website, you talk about being interested in writing fiction from an early age but that you had to write nonfiction to earn money consistently. How would you describe the differences between fiction and nonfiction writing. Do have to get into a different mindset to write fiction?

To answer this, I’d like to share the teaser copy for a profile* I wrote:

"There have been young violinists in my house for 14 years, so I was well-acquainted with Philipp Naegele’s reputation as an outstanding string teacher. I knew he was on the faculty of the music department of Smith College, and that he was associated with the Marlboro Music School & Festival in Vermont. I even knew, vaguely, that he’d once done a lot of recording. But the first time we spoke face to face, when he let drop that he’d come to England from Germany in 1939, alone, at the age of 11, all those other facts fell away before this image of a young boy, forced to flee his homeland, with only his violin and his music to sustain him. I was compelled to dig further, to discover the deeper qualities of the man suggested by that image. A life of courage, determination—and love—was what I unearthed."

For me, all writing starts from this point: Someone shares their experience or I witness something and it resonates. I’m moved to tears or laughter or reflection. Whether fiction or nonfiction, I have only ever pitched stories for which I have an emotional affinity. Stories I believe in. My published short fiction includes stories about a man coming to terms with fatherhood after a life of drifting, and a long-anticipated family outing that reveals the emptiness of endless consumption My published work for magazines and newspapers includes articles about empowering our daughters and the need for stricter gun laws. So, from that angle, I don’t approach nonfiction differently from fiction.

Obviously, issues of voice, style, even grammar and syntax, play out differently—fiction tends to allow far greater freedom in these areas than nonfiction. But all writing requires a reason to be. It’s finding and understanding that reason that drives the writing for me.

While my writing is almost exclusively for children, Amy writes for an adult audience. You can read a teaser for her intriguing WWII novel, The Sticking Place, on her website https://amyhenrybooks.com/about-the-bookexcerpt/ You’ll also find links to two of her published short stories here: https://amyhenrybooks.com/publications-awards/

--------------------------

So ... Amy ...

Thanks for letting me interview you. The reason I've dragged you into this is to pick your brain about writing.

Q: On your website, you talk about being interested in writing fiction from an early age but that you had to write nonfiction to earn money consistently. How would you describe the differences between fiction and nonfiction writing. Do have to get into a different mindset to write fiction?

To answer this, I’d like to share the teaser copy for a profile* I wrote:

"There have been young violinists in my house for 14 years, so I was well-acquainted with Philipp Naegele’s reputation as an outstanding string teacher. I knew he was on the faculty of the music department of Smith College, and that he was associated with the Marlboro Music School & Festival in Vermont. I even knew, vaguely, that he’d once done a lot of recording. But the first time we spoke face to face, when he let drop that he’d come to England from Germany in 1939, alone, at the age of 11, all those other facts fell away before this image of a young boy, forced to flee his homeland, with only his violin and his music to sustain him. I was compelled to dig further, to discover the deeper qualities of the man suggested by that image. A life of courage, determination—and love—was what I unearthed."

For me, all writing starts from this point: Someone shares their experience or I witness something and it resonates. I’m moved to tears or laughter or reflection. Whether fiction or nonfiction, I have only ever pitched stories for which I have an emotional affinity. Stories I believe in. My published short fiction includes stories about a man coming to terms with fatherhood after a life of drifting, and a long-anticipated family outing that reveals the emptiness of endless consumption My published work for magazines and newspapers includes articles about empowering our daughters and the need for stricter gun laws. So, from that angle, I don’t approach nonfiction differently from fiction.

Obviously, issues of voice, style, even grammar and syntax, play out differently—fiction tends to allow far greater freedom in these areas than nonfiction. But all writing requires a reason to be. It’s finding and understanding that reason that drives the writing for me.

The D-Day Landings at Normandy

Q: Your novel, The Sticking Place, is set in WWII and is about a bright young woman eager to make her mark on the world. She goes to England’s Bletchley Park to work for the Allies as a cryptanalyst, but soon finds herself embroiled in something darker. How are you approaching the process of querying agents for this project? Do you have plans to revise the novel?

A: My novel is historical suspense (with a romantic subplot), which, in terms of agents, is not as straightforward as, say, mystery or romance. I research potential agents pretty thoroughly. Google the interviews. Read up on some of the books/clients they represent. I try to get a feeling for why I might want to work with a particular agent and why they might be interested in me. In my search, I’ve discovered any number of lovely-seeming literary agents, but they want a whodunnit or steampunk or fantasy, and that’s not what I’m doing.

As far as the query process, I take it slow. I know authors who blanket query—a hundred or more agents at once—and some of them have been very successful in getting an agent this way. It’s certainly more expedient from the author’s viewpoint. But I view querying, partly, as a discovery process. Is my query letter effective? How are agents responding to sample chapters? Are they requesting the full, but then not committing to representation?

I’ve shopped The Sticking Place to a handful of agents. The feedback confirmed that the query, synopsis, and sample chapters work. The general feedback on the full manuscript was: “Love the writing. Love the protagonist. The suspense elements get too complicated. Got anything else I can look at?” So, I stopped querying and overhauled the book, focusing on the feedback that several agents were kind enough to detail. I’m preparing for another round of queries on the revised manuscript.

I love that the computer allows a writer to completely rip a chapter, or the entire book, and experiment with every aspect, knowing there’s a copy of the original on file. As a writer, I can’t imagine anything more freeing.

A: My novel is historical suspense (with a romantic subplot), which, in terms of agents, is not as straightforward as, say, mystery or romance. I research potential agents pretty thoroughly. Google the interviews. Read up on some of the books/clients they represent. I try to get a feeling for why I might want to work with a particular agent and why they might be interested in me. In my search, I’ve discovered any number of lovely-seeming literary agents, but they want a whodunnit or steampunk or fantasy, and that’s not what I’m doing.

As far as the query process, I take it slow. I know authors who blanket query—a hundred or more agents at once—and some of them have been very successful in getting an agent this way. It’s certainly more expedient from the author’s viewpoint. But I view querying, partly, as a discovery process. Is my query letter effective? How are agents responding to sample chapters? Are they requesting the full, but then not committing to representation?

I’ve shopped The Sticking Place to a handful of agents. The feedback confirmed that the query, synopsis, and sample chapters work. The general feedback on the full manuscript was: “Love the writing. Love the protagonist. The suspense elements get too complicated. Got anything else I can look at?” So, I stopped querying and overhauled the book, focusing on the feedback that several agents were kind enough to detail. I’m preparing for another round of queries on the revised manuscript.

I love that the computer allows a writer to completely rip a chapter, or the entire book, and experiment with every aspect, knowing there’s a copy of the original on file. As a writer, I can’t imagine anything more freeing.

RAF boys, Battle of Britain

Q: Historical fiction requires a humongous amount of research! Could you describe your research process.

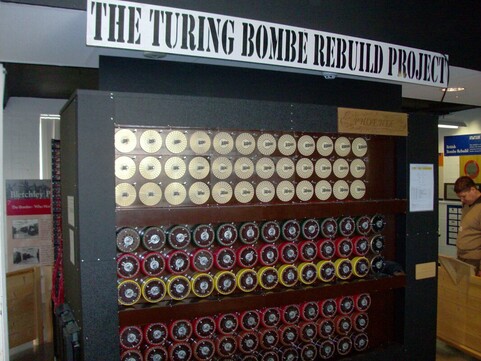

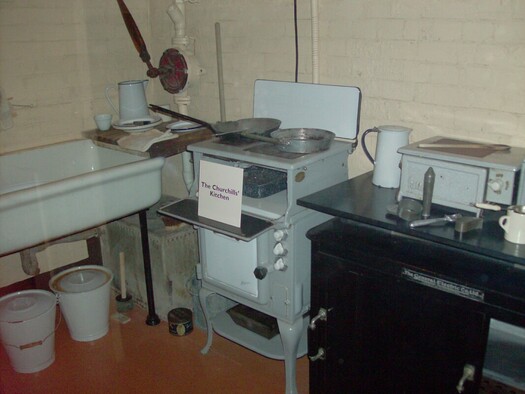

A: Process may be too tidy a word for it. The Sticking Place was born from reading a book on Wilhelm Canaris, the head of the Abwehr (German military intelligence). I found myself talking about him to anyone who would listen. Then I found my “core sourcebook” (I find every novel I write has one), in this case Maureen Waller’s London 1945, and I visited Bletchley Park several times. Always fascinated by WWII—its great scope for reflecting on human courage and hope as well as the depths of human depravity—I started getting these characters in my head. As I imagined them in wartime London and the challenges they faced, the plot gained definition and I just went wherever I needed to in terms of research. I did reams of research on Hitler’s vengeance weapons. These were a BIG DEAL. The stuff of science fiction come to life. I also learned a great deal about WWII aircraft, the SOE (Special Operations Executive), codebreaking, and the daily life of British civilians in wartime. It always helps to see a place you’re writing about, so I visited the Savoy Hotel in London and talked to an elderly man who had worked in the hotel’s American Bar during the war. The Covent Garden Opera House showed me photos of the wartime dances in that venue—they laid a dance floor on top of the seats and brought in bands. I also corresponded with a man on the West Coast to learn about parachutes of the era because I have a character dropped behind enemy lines.

The trick about historical research is to let it infuse the novel rather than overwhelm it. I would estimate that only about 5% of my total research “shows up” in the story, but every page is immersed in the times because of it.

All that said, contemporary fiction can also require research. In the novel I just completed, the action occurs from 1980-2021. It still required a lot of research—legal issues, chemical toxins, child welfare work, Senate and House procedures, and a lengthy list of other stuff. I just google, and then google some more, and then check in with real life experts where required. Good thing I like research because writing tends to demand lots of it.

A: Process may be too tidy a word for it. The Sticking Place was born from reading a book on Wilhelm Canaris, the head of the Abwehr (German military intelligence). I found myself talking about him to anyone who would listen. Then I found my “core sourcebook” (I find every novel I write has one), in this case Maureen Waller’s London 1945, and I visited Bletchley Park several times. Always fascinated by WWII—its great scope for reflecting on human courage and hope as well as the depths of human depravity—I started getting these characters in my head. As I imagined them in wartime London and the challenges they faced, the plot gained definition and I just went wherever I needed to in terms of research. I did reams of research on Hitler’s vengeance weapons. These were a BIG DEAL. The stuff of science fiction come to life. I also learned a great deal about WWII aircraft, the SOE (Special Operations Executive), codebreaking, and the daily life of British civilians in wartime. It always helps to see a place you’re writing about, so I visited the Savoy Hotel in London and talked to an elderly man who had worked in the hotel’s American Bar during the war. The Covent Garden Opera House showed me photos of the wartime dances in that venue—they laid a dance floor on top of the seats and brought in bands. I also corresponded with a man on the West Coast to learn about parachutes of the era because I have a character dropped behind enemy lines.

The trick about historical research is to let it infuse the novel rather than overwhelm it. I would estimate that only about 5% of my total research “shows up” in the story, but every page is immersed in the times because of it.

All that said, contemporary fiction can also require research. In the novel I just completed, the action occurs from 1980-2021. It still required a lot of research—legal issues, chemical toxins, child welfare work, Senate and House procedures, and a lengthy list of other stuff. I just google, and then google some more, and then check in with real life experts where required. Good thing I like research because writing tends to demand lots of it.

Alan Turing's bombe machines that broke the Enigma code

Q: I find that the average American's knowledge of history is appalling. Most students don't like history. I know you were formerly a teacher, and you love history as much as I do. How do you think history could be taught in more interesting ways?

A: Understanding history is crucial. Without it, we’re just a bunch of errant pinballs ricocheting from place to place until Game Over. More darkly, as the philosopher George Santayana warned, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

I taught elementary kids, but even at that age, you can get students interested in the past. For my master teaching unit, I had to pick a state learning standard and build curriculum around it. I chose Change Over Time. Because my students were second-graders, we built on what they knew: Our town. I found photographs from the 19th and early 20th centuries of the downtown, university campus, and surrounding neighborhoods. We visited these places and made notes about how they had changed. We discussed why these changes had occurred, what technologies had emerged, and what needs developed from these changes that fueled further changes. One example was the emergence of automobiles. They completely altered the landscape, of course, but also the idea that one would be born, grow up, and die all within the same town. For my students, some who had moved five or six times already in their short lives, some who had come from as far away as Viet Nam, this was an arresting idea.

Another project I did when I had my own classroom was biography-writing. It got my first-graders talking to their parents and grandparents about “the way things used to be.” The kids embraced it. I think we all want to know where we come from, how the world before us was both different and the same.

A: Understanding history is crucial. Without it, we’re just a bunch of errant pinballs ricocheting from place to place until Game Over. More darkly, as the philosopher George Santayana warned, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

I taught elementary kids, but even at that age, you can get students interested in the past. For my master teaching unit, I had to pick a state learning standard and build curriculum around it. I chose Change Over Time. Because my students were second-graders, we built on what they knew: Our town. I found photographs from the 19th and early 20th centuries of the downtown, university campus, and surrounding neighborhoods. We visited these places and made notes about how they had changed. We discussed why these changes had occurred, what technologies had emerged, and what needs developed from these changes that fueled further changes. One example was the emergence of automobiles. They completely altered the landscape, of course, but also the idea that one would be born, grow up, and die all within the same town. For my students, some who had moved five or six times already in their short lives, some who had come from as far away as Viet Nam, this was an arresting idea.

Another project I did when I had my own classroom was biography-writing. It got my first-graders talking to their parents and grandparents about “the way things used to be.” The kids embraced it. I think we all want to know where we come from, how the world before us was both different and the same.

Q: Have you ever thought about writing for children/teens?

A: I’ve actually written several YA books—one contemporary, one historical—which I may someday polish up and submit. I enjoy writing for that age group because the universal twin themes of finding one’s identity and letting go of the shelter of childhood—making those first tentative steps onto a stage where you will become responsible for your own life—offer extraordinarily rich material. I never decided to stop writing YA. I just became interested in other themes and stories. That said, I treasure the connections and friends I made when I was an SCBWI member. The critique groups I participated in with those writers were the most productive I’ve ever experienced.

A: I’ve actually written several YA books—one contemporary, one historical—which I may someday polish up and submit. I enjoy writing for that age group because the universal twin themes of finding one’s identity and letting go of the shelter of childhood—making those first tentative steps onto a stage where you will become responsible for your own life—offer extraordinarily rich material. I never decided to stop writing YA. I just became interested in other themes and stories. That said, I treasure the connections and friends I made when I was an SCBWI member. The critique groups I participated in with those writers were the most productive I’ve ever experienced.

The kitchen in Churchill's WWII underground bunker at Whitehall

Q: Is there anything else you'd like to say to writers who are struggling with the craft?

A: Keep going. If you yearned to dance the ballet, you would take years of classes. If you wanted to be an electrician, you’d serve a lengthy apprenticeship. But for writers, our training is in the books we read. Our apprenticeship, in the essays, short stories, and novels we write (and rewrite). Critique groups are great—I’ve been in a number of them. Conferences provide wonderful opportunities to be with others who share your goals and struggles. But, in the end, it’s you and your words. To riff on the old Peace Corps ad: Writing is the toughest job you’ll ever love. It’s a good day when you get a request for your full manuscript. It’s something to celebrate when you sign with an agent or an editor. But don’t forget that, like all the great artists who drew thousands of figures before painting a masterpiece, nothing you write is ever a waste. You are always in the process of becoming.

“Music Has Sustained Him.” Hampshire Life. January 26, 2007.

----------------------------

Thanks, Amy, for taking the time to share your writing insights!

A: Keep going. If you yearned to dance the ballet, you would take years of classes. If you wanted to be an electrician, you’d serve a lengthy apprenticeship. But for writers, our training is in the books we read. Our apprenticeship, in the essays, short stories, and novels we write (and rewrite). Critique groups are great—I’ve been in a number of them. Conferences provide wonderful opportunities to be with others who share your goals and struggles. But, in the end, it’s you and your words. To riff on the old Peace Corps ad: Writing is the toughest job you’ll ever love. It’s a good day when you get a request for your full manuscript. It’s something to celebrate when you sign with an agent or an editor. But don’t forget that, like all the great artists who drew thousands of figures before painting a masterpiece, nothing you write is ever a waste. You are always in the process of becoming.

“Music Has Sustained Him.” Hampshire Life. January 26, 2007.

----------------------------

Thanks, Amy, for taking the time to share your writing insights!